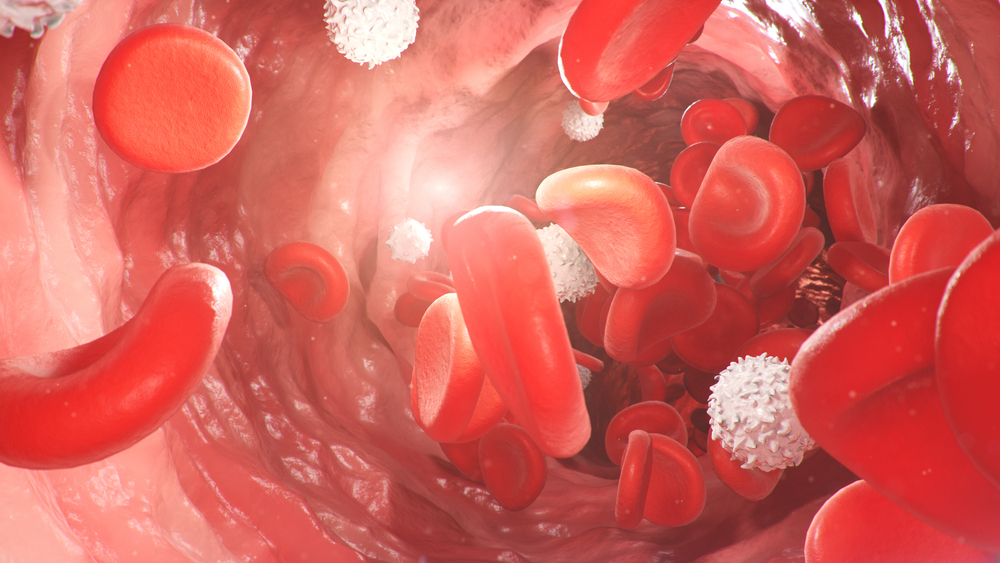

Red Blood Cells (RBCs) are the most common type of blood cell – they make up almost half of your blood - and they play an essential role in carrying oxygen. All cells in every part of your body need oxygen to make energy so that they can function properly.

RBCs can carry oxygen because they contain haemoglobin. Haemoglobin is the red protein in RBCs that gives them their colour. Oxygen sticks to the haemoglobin in RBCs so it can be transported.

If your haemoglobin levels are low, or if you have too few RBCs, your body will not be able to get enough oxygen, causing fatigue and weakness.

What are reticulocytes?

To stay healthy, your body must make new RBCs to replace those that age and degrade or are lost through bleeding.

Blood cells are continually being renewed. New cells are produced in the bone marrow, the soft fibrous tissue inside many bones, and then released into your blood stream. RBCs typically survive for about 120 days in circulation.

RBCs develop from stem cells into mature cells through several stages. Reticulocytes are cells in the final stage of red cell development, just before mature RBCs are released into the blood.

Most RBCs are fully mature before they are released but a tiny percentage are released into the blood as reticulocytes.

Unlike most other cells in the body, mature RBCs have no nucleus – this is the structure inside sells that contains genes - but reticulocytes still have some remnant genetic material (RNA). As reticulocytes mature, they lose the last RNA, and most are fully developed within one day of being released from the bone marrow into the blood.

The reticulocyte count is a good indicator of the ability of your bone marrow to adequately produce RBCs.

When you lose too many red blood cells

The body tries to maintain a stable number of RBCs in circulation by continually removing old RBCs and producing new ones in the bone marrow.

Loss of RBCs may be due to acute or chronic bleeding or haemolysis, a condition in which red blood cells are destroyed. If this occurs faster than the body can replace them, this can lead to haemolytic anaemia.

There are many causes of haemolytic anaemia including inherited or acquired conditions such as infection, medications and autoimmune condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks itself. Haemolytic disease of the newborn is a condition where a baby’s RBCs are destroyed by antibodies from the mother. This leads to anaemia and jaundice in the baby.

The body compensates for the loss of RBCs by increasing the rate of production of RBCs in the bone marrow and releasing RBCs sooner into the blood before they have fully matured.

This means the number and percentage of reticulocytes in the blood increase until enough RBCs replace those that were lost or until the production capacity of the bone marrow is reached.

Causes include:

When you don’t make enough red blood cells

This can happen when your body does not have the raw materials it needs to make RBCs and haemoglobin. This can be due to deficiencies in iron, folate or vitamin B12.

It can also be caused by health disorders such a coeliac disease that affect your intestines’ ability to absorb essential nutrients.

It can also be caused by chronic kidney disease. Erythropoietin is a hormone made in the kidneys that stimulates the production of RBCs in the bone marrow. Kidney disease can reduce the amount of erythropoietin being made and this reduces RBC production.

Health disorders that affect the bone marrow such as aplastic anaemia and leukaemia can also prevent your body from making enough RBCs. Causes include:

When you make too many red blood cells

If you have too many RBCs, you are said to have polycythaemia. This makes your blood thicker than it should be, and without treatment it can increase your risk of blood clots.

There are two types of polycythaemia:

A reticulocyte count is often ordered when the Full Blood Count (FBC), a test used as a routine health check, has shown your red blood cell levels are not normal – either too high or too low.

It is also used to help tell the difference between types of anaemia, to monitor response to treatment, and to monitor bone marrow function following treatments such as chemotherapy.

Sample

Blood.

Any preparation?

None.

Reading your test report

Your results will be presented along with any other tests your doctor ordered on the same form. You will see separate columns or lines for each of these tests. Your results may be flagged as high (H) or low (L).

Results of the reticulocyte count must be interpreted along with the results of other tests, such as a red blood cell count, haemoglobin and haematocrit, which are included in the Full Blood Count (FBC).

In general, the reticulocyte count reflects recent bone marrow activity. Results can give an indication of what may be happening, but they are not diagnostic of any particular disorder. They can help decide if further investigation is needed.

In some cases, a procedure called a bone marrow aspiration may be performed to obtain a sample of marrow to evaluate under the microscope. Sometimes this is the best way to determine how well the bone marrow is functioning.

| Reticulocyte levels | Haemoglobin levels | Interpretation |

| Low | Low | The results of your haemoglobin test will tell if you have anaemia. The results of your reticulocyte count will show how your bone marrow is responding and if it is adequately replacing RBCs. If you have low haemoglobin and low reticulocyte count your bone marrow is not making enough RBCs. |

| High | Low | A low haemoglobin and high reticulocyte count shows that your bone marrow is responding and producing more RBCs in an attempt to compensate for the anaemia. |

| High | High | If you have a high haemoglobin level and a high reticulocyte count your bone marrow is producing too many RBCs. This can be due to polycythaemia. |

| Rising following treatment | N/A | RBC production is beginning to recover. |

The number of reticulocytes is compared to the total number of RBCs to calculate the percentage of reticulocytes. The reticulocyte count in a healthy adult should be between 0.5 to 2.5 per cent. | ||

Reference intervals - comparing your results to the healthy population

Your results will be compared to reference intervals (sometimes called a normal range).

If your results are flagged as high or low this does not necessarily mean that anything is wrong. It depends on your personal situation.

The choice of tests your doctor makes will be based on your medical history and symptoms. It is important that you tell them everything you think might help.

You play a central role in making sure your test results are accurate. Do everything you can to make sure the information you provide is correct and follow instructions closely.

Talk to your doctor about any medications you are taking. Find out if you need to fast or stop any particular foods or supplements. These may affect your results. Ask:

Pathology and diagnostic imaging reports can be added to your My Health Record. You and your healthcare provider can now access your results whenever and wherever needed.

Get further trustworthy health information and advice from healthdirect.