Bone marker tests measure substances in the blood and urine that are produced as bones remodel themselves as part of the natural regeneration cycle.

They are used to evaluate and monitor the rate of bone resorption and formation. They can help in the diagnosis of age-related bone loss conditions such as osteoporosis as well as disorders such as Paget’s disease, osteomalacia, cancer, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, chronic kidney failure and Cushing’s syndrome.

They are also useful in monitoring the effectiveness of treatment. However, they are not diagnostic and cannot show the cause of a health problem. They offer additional information to the doctor but do not take the place of bone mineral density screening.

Bone marker tests measure substances in the blood and urine that are produced as bones remodel themselves as part of the natural regeneration cycle.

They are used to evaluate and monitor the rate of bone resorption and formation. They can help in the diagnosis of age-related bone loss conditions such as osteoporosis as well as disorders such as Paget’s disease, osteomalacia, cancer, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, chronic kidney failure and Cushing’s syndrome.

They are also useful in monitoring the effectiveness of treatment. However, they are not diagnostic and cannot show the cause of a health problem. They offer additional information to the doctor but do not take the place of bone mineral density screening.

What is being tested?

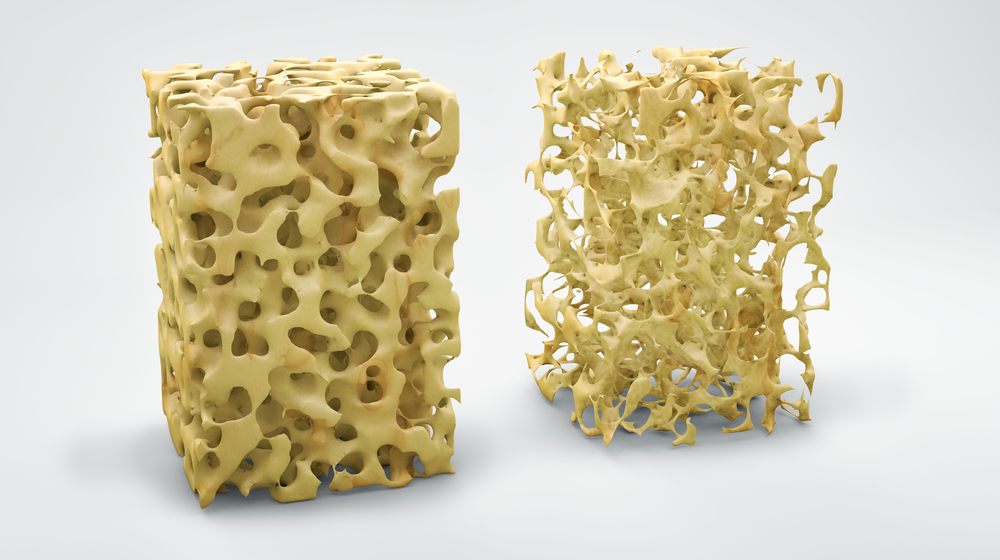

Bone is the rigid, hard connective tissue that comprises the majority of the skeleton in humans. It is a living, growing tissue that turns over at a rate of about 10% a year. Bone markers are blood and urine tests that detect products of bone remodelling to help determine if the rate of bone resorption and/or formation is abnormally increased, suggesting a potential bone disorder. The markers can be used to help determine a person's risk of bone fracture and to monitor drug therapy for people receiving treatment for skeletal disorders including osteoporosis.

Bone is made up largely of type-I collagen, a protein network that gives the bone its tensile strength and framework, and calcium phosphate, a mineralised complex that hardens the skeletal framework. This combination of collagen and calcium gives bone its hardness, and yet bones are flexible enough to bear weight and withstand stress. More than 99% of the body's calcium is contained in the bones and teeth. Most of the remaining 1% is found in the blood.

Throughout a person's lifetime, bone is constantly being remodelled to maintain a healthy bone structure that conforms to the person's needs. There are two major types of cells within bone: osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Osteoblasts are the cells that lay down new bone, but they first initiate bone resorption by stimulating osteoclasts, which dissolve small amounts of bone in the area that needs strengthening using acid and enzymes to dissolve the protein network.

Osteoblasts then initiate new bone formation by secreting a variety of compounds that help form a new protein network, which is then mineralised with calcium and phosphate. This on-going remodelling process takes place on a microscopic scale throughout the body to keep bones alive and sturdy.

During early childhood and in the teenage years, new bone is added faster than old bone is removed. As a result, bones become larger, heavier, and denser. Bone formation happens faster than bone resorption until a person reaches their peak bone mass (maximum bone density and strength) between the ages of 25 and 30 years. After this peak period, bone resorption occurs faster than the rate of bone formation, leading to net bone loss. The age at which an individual begins to experience symptoms of bone loss depends on the amount of bone that was developed during their youth and the rate of bone resorption. Traditionally, women exhibit these symptoms earlier than men because they may not have developed as much bone during the peak years and, after menopause, rate of bone loss is accelerated in some women.

Several diseases and conditions can cause an imbalance between bone resorption and formation, and bone markers can be useful in detecting the imbalance and bone loss. Most often, the markers have been studied in the evaluation and monitoring of osteoporosis, including age-related osteoporosis or secondary osteoporosis, which is bone loss due to an underlying condition. Bone loss may result from conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing disease, chronic kidney disease, multiple myeloma, or from prolonged use of drugs such as anti-epileptics, glucocorticoids, or lithium.

Below is a list of some bone resorption and formation markers measured in blood and/or urine samples. Research is ongoing for new biomarkers that can predict abnormal bone loss in various disease states. For many of these markers, caution is required in interpreting test results as they can be affected by diet, exercise, and time of day the sample is collected.

How is it used?

One or more of the bone marker tests may be used to help determine if a person has increased rates of bone turnover (resorption and/or formation). Bone markers are sometimes used as an adjunct to bone mineral density (BMD) testing (e.g., by DEXA scan) to help evaluate bone loss and detect some bone diseases. They often are used to monitor response to anti-resorptive therapy for bone disease, primarily osteoporosis, and to help a doctor determine if the dose of the drug a person is receiving is effective.

These tests can detect response to anti-resorption or bone building therapies in a much shorter time period than BMD testing (three to six months versus one to two years). This way, therapy can be adjusted or altered in a more timely manner if a person is not responding as expected.

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry & Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) recommend two blood tests for evaluating bone turnover:

Other urine or blood tests used less commonly for bone resorption include:

Other bone formation blood tests that may sometimes be used include:

When is it requested?

Testing may be performed along with other tests such as a calcium, vitamin D, thyroid testing, and parathyroid hormone when bone loss is detected during a bone mineral density test (diagnostic imaging) and/or when a person has a history of unexpected bone fracture.

One or more bone marker tests may be performed prior to anti-resorptive or bone formation therapy and then typically 3 to 6 months later to monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

What does the result mean?

A high level of one or more bone markers in urine and/or blood suggests an increased rate of resorption and/or formation of bone, but it does not indicate the cause (it is not diagnostic). An elevated level of bone markers may be seen in conditions such as:

A low or normal level suggests no excessive bone turnover.

When used to monitor anti-resorptive therapy, decreasing levels of the bone resorption markers over time reflect a response to therapy.

Is there anything else I should know?

Samples must be consistently collected, and test results must be interpreted with caution. There is both day-to-day variability in bone marker concentrations and diurnal variation (changes throughout the day). Most bone marker concentrations will be the highest in the morning, and some, in particular, C-telopeptide, are affected by eating.

Concentrations of bone markers are affected by a variety of factors, particularly during childhood development. These include age, sex, growth velocity, nutritional status, and puberty. Therefore, interpretation of bone marker results requires use of appropriate reference intervals.

Most people with bone loss are not aware of it. The condition may not cause any symptoms until a person has an unexpected bone fracture.

There are limitations to the clinical utility of many of these bone markers, but researchers continue to explore ways to improve their clinical use. Their principal use is to gauge the effectiveness of the therapies used to treat metabolic bone disease and to properly adjust the dose for maximal effect.

Common questions

Bone marker testing is typically only indicated in those who have been diagnosed with or are at risk of bone loss. The tests are not intended to be used to screen the general public. They offer additional information to the doctor but do not take the place of bone mineral density screening.

Typically, no one will have all of the tests done that are described here. Most doctors use one or a few particular bone markers, including one or two that evaluate bone resorption and one or two that evaluate bone formation. The choice of bone markers will depend on many factors, including your medical history, signs and symptoms, and physical examination, and these all vary from person to person. Your doctor will make the selection based on the usefulness of the tests for your condition. In general, if a test is ordered as a baseline prior to therapy, then the same test will be ordered later so that the two results can be compared.

In general, no. While a blood or urine sample may be collected in your doctor's office, the sample will be sent to a laboratory for testing. Bone marker testing is not offered by all laboratories and will often be sent to a reference laboratory.

People can and should take steps to maintain bone health throughout their life, but bone markers themselves are not affected by lifestyle changes. If you have bone loss, work with your healthcare practitioner to determine the best treatment for you.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and related drugs such as raloxifene can help maintain bone density in women after the menopause. Bisphosphonates, such as alendronate, also help to maintain bone density and prevent fractures, and the hormone calcitonin can be used to prevent bone resorption. Alternative treatments such as strontium ranelate taken as a daily drink increase bone mass, zoledronic acid given as a once yearly infusion and denosumab given as a 6 monthly injection, are also effective treatments. The most appropriate option will need to be discussed with your doctor.

The condition may affect up to 2 million people in Australia but many will not know they have the disease. Of the people with osteoporosis, 80% are women.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.