What is being tested?

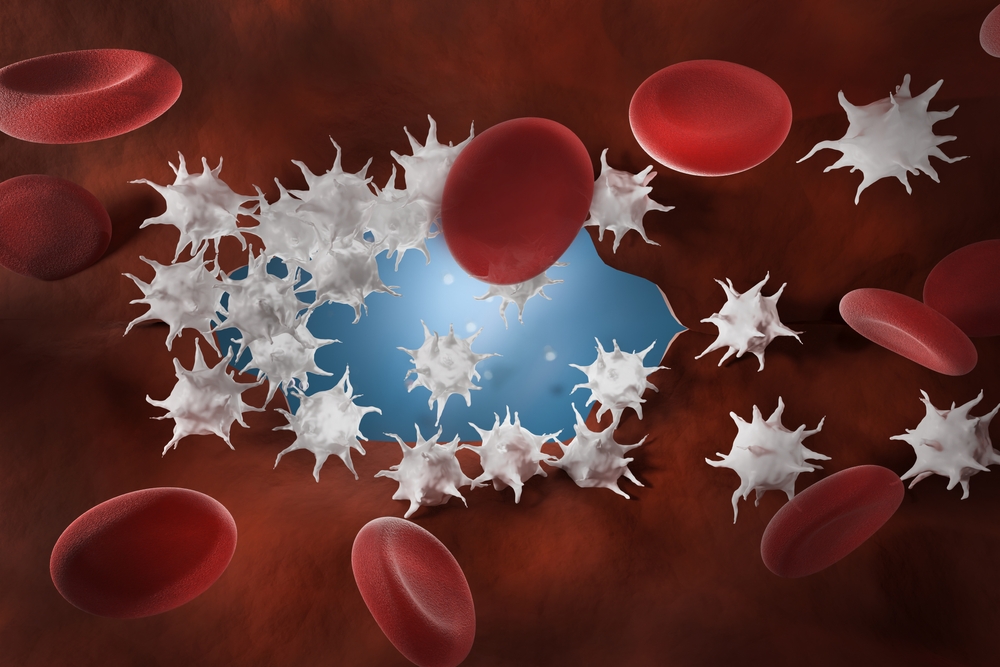

What happens when an injury occurs? Fibrinogen is a coagulation factor, a protein that is essential for blood clot formation. It is produced by the liver and released into the circulation as needed along with over 20 other clotting factors. Normally, when a body tissue or blood vessel wall is injured a process called the coagulation cascade activates these factors. As the cascade nears completion, soluble fibrinogen (fibrinogen dissolved in fluid) is changed into insoluble fibrin threads which form a mesh-like structure. The fibrin mesh along with aggregated cell fragments called platelets, forms a stable blood clot. This barrier prevents additional blood loss and remains in place until the area has healed.

Coagulation tests are based on what happens in the test setting (in vitro) and thus does not exactly reflect what is actually happening in the body (in vivo). Nevertheless, the tests can be used to evaluate specific components of the haemostasis system.

Two types of tests are available to evaluate fibrinogen:

How is it used?

Fibrinogen activity test is used as part of an investigation of a possible bleeding disorder or inappropriate blood clot formation. Fibrinogen is usually requested with other tests such as PT, APTT, platelets, fibrin degradation products (FDP), and D-dimer to help diagnose disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Fibrinogen may be used as a follow-up to an abnormal prothrombin time (PT) or activated partial prothrombin time (APTT, or PTT) and/or an episode of prolonged or unexplained bleeding. Occasionally fibrinogen can be used to help monitor the status of a progressive disease (such as liver disease) over time.

Sometimes fibrinogen is requested with other cardiac risk markers such as C-reactive protein high sensitivity (hsCRP), to help determine a patient's overall risk of developing cardiovascular disease. This use of measuring fibrinogen levels has not gained widespread acceptance though, because there are no direct treatments for elevated levels. However, some doctors feel fibrinogen measurements give them additional information that may lead them to be more aggressive in treating those risk factors that they can influence (such as cholesterol and HDL).

Fibrinogen antigen test can be ordered as a follow-up test to determine if decreased activity is caused by insufficient fibrinogen or dysfunctional fibrinogen.

When is it requested?

The doctor may request a fibrinogen test when a patient has unexplained or prolonged bleeding and/or an abnormal PT and APTT test result. The test can also be used when patients have symptoms of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), such as: bleeding gums, nausea, vomiting, severe muscle and abdominal pain, seizures and oliguria (decreased urine output), or when the doctor is monitoring treatment for DIC.

Fibrinogen testing can also be performed with other coagulation factor tests when there is suspicion that the patient may have an inherited factor deficiency or dysfunction, or when the doctor wants to evaluate and monitor over a period of time the clotting ability of a patient with an acquired bleeding disorder.

In some cases, fibrinogen testing is performed with other tests when the doctor wants to evaluate a patient's risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

What does the result mean?

Fibrinogen levels are a reflection of clotting ability and activity in the body. Reduced concentrations of fibrinogen may impair the body's ability to form a stable blood clot. Very low levels may be related to decreased production due to an inherited condition such as afibrinogenaemia (no production) or hypofibrinogenaemia (low levels), or to an acquired condition such as liver disease or malnutrition.

Acutely (occurring suddenly) low levels are often related to consumption of fibrinogen, such as may be seen with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). These conditions use up large amounts of clotting factors, leading first to inappropriate clot formation then - as levels fall - to excessive bleeding. Reduced fibrinogen levels may also be seen, sometimes, following large volume blood loss (for example after a motor vehicle accident). Fibrinolytic proteins that normally dissolve clots, may also reduce fibrinogen levels by both attacking fibrinogen and breaking down fibrin at an accelerated rate.

Normal fibrinogen levels usually reflect normal clotting, but may also be seen when a person has a sufficient quantity of fibrinogen, but the fibrinogen is not functioning normally – called dysfibrinogenaemia. This is usually due to a rare inherited abnormality in the gene that produces fibrinogen, which leads to the production of an abnormal fibrinogen protein. If clinical findings suggest a fibrinogen problem, other specialised tests may be done to evaluate fibrinogen function further.

Fibrinogen concentrations may rise sharply in any condition that causes inflammation, tissue damage or stress, such as surgery or inflammatory illnesses. Elevated concentrations of fibrinogen are not specific - they do not tell the doctor the cause or location of the disturbance. For this reason, doctors often do not check for elevated fibrinogen levels in these situations. Usually these elevations are temporary; returning to normal after the underlying condition has been resolved.

Elevated levels may be seen with:

While fibrinogen levels are elevated, they may increase a person's risk of developing a blood clot and over time they could contribute to an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease. This is why some doctors occasionally request fibrinogen with other cardiac risk markers.

Is there anything else I should know?

Blood transfusions within the past month may affect fibrinogen test results. Certain drugs may cause decreased levels, including: anabolic steroids, androgens, phenobarbital, fibrinolytic drugs (streptokinase, urokinase, tPA) and sodium valproate. Moderate elevations in fibrinogen may be seen sometimes with pregnancy, cigarette smoking, and with oral contraceptives or oestrogen use.

Dysfibrinogenaemia (abnormal fibrinogen production), is a rare coagulation disorder caused by a mutation in the gene controlling the production of fibrinogen in the liver. It causes the liver to make an abnormal fibrinogen, one that may resist degradation when converted to fibrin and be associated predominantly with venous thrombosis (inappropriate blood clot formation in the veins). PT, APTT, and thrombin time are used to screen for this condition which is then confirmed with additional specialised blood tests. Alternatively, patients with fibrinogen deficiency or dysfibrinogenaemia may experience poor wound healing and increased bleeding.

Common questions

If your fibrinogen concentration is elevated due to pregnancy, or to an acute inflammatory process, it will usually return to normal by itself. If it is due to an acquired condition such as rheumatoid arthritis, there may be very little you can do to affect the level. If your doctor has told you that elevated fibrinogen levels are increasing your risk of cardiovascular disease, you can make lifestyle changes, such as stop smoking, lose weight, increase exercise, reducing your cholesterol and raising your HDL. There is also some evidence that diets rich in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids (fish oils) may help reduce fibrinogen levels.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.