What is being tested?

This test measures the level of sodium in blood. Sodium is an electrolyte present in all body fluids and is vital to normal body function. It works to regulate the amount of water in the body, and to control blood pressure by keeping the right amount of water available (in some people, too much sodium from salt in the diet can contribute to high blood pressure). Your body tries to keep your blood sodium within a very small concentration range; it does so by:

Abnormal blood sodium is usually due to some problem with one of these systems. When the level of sodium in the blood changes, the water content in your body changes. These changes can be associated with dehydration (too little fluid) or oedema (too much fluid, often resulting in swelling in the legs).

How is it used?

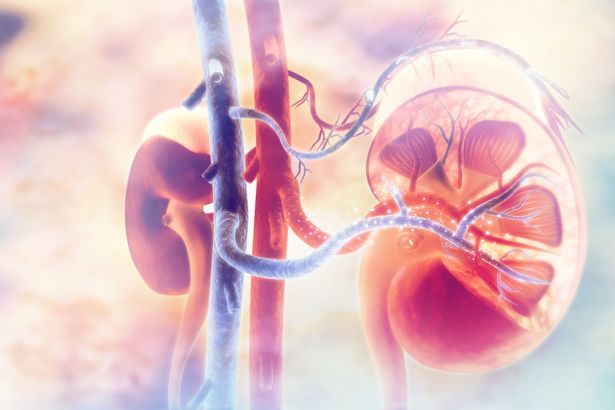

Blood sodium is used to detect the cause and help monitor treatment in persons with dehydration, oedema, or with a variety of symptoms. Blood sodium is abnormal in many diseases; your doctor may request this test if you have symptoms of illness involving the brain, lungs, liver, heart, kidney, thyroid, or adrenal glands.

Urine sodium levels are typically tested in patients who have abnormal blood sodium levels, to help determine whether an imbalance is due to taking in too much sodium or losing too much sodium. Urine sodium is also used to see if a person with high blood pressure is eating too much salt and is also often used in persons with abnormal kidney tests to help the doctor determine the cause of kidney disease, which can help to guide treatment.

When is it requested?

This test is a part of the routine laboratory evaluation of most patients. It is one of the blood electrolytes, which are often requested as a group when someone has non-specific health complaints. It is also tested when monitoring treatment involving intravenous (IV) fluids or when there is a possibility of developing dehydration. Electrolytes are also commonly used to monitor treatment of certain problems, including high blood pressure, heart failure and liver and kidney disease.

What does the result mean?

Sodium is often included in groups of tests used to monitor kidney and other body functions. Sodium is the major electrolyte in all the body fluids outside the cells. The amount of sodium and water in these extracellular fluids are closely related and gains or losses of either can affect the other so they need to be considered together. If sodium levels go too low or too high, your health may suffer.

A low level of blood sodium is called hyponatraemia, and is usually due to either too much sodium loss, too much water intake or retention, or fluid accumulation in the body (oedema). If sodium falls quickly, you may feel weak and tired; in severe cases, you may experience confusion or even fall into a coma. When sodium falls slowly, however, there may be no symptoms. That is why sodium levels are often checked even if you don't have any symptoms.

Hyponatraemia is rarely due to decreased sodium intake (deficient dietary intake or deficient sodium in IV fluids). Most commonly, it is due to sodium loss (diarrhoea, vomiting, excessive sweating, diuretic administration, kidney disease or Addison's disease). In some cases, it is due to excess fluids in the body (drinking too much water, heart failure, cirrhosis, kidney diseases that cause protein loss [nephrotic syndrome]) and malnutrition. In a number of diseases (particularly those involving the brain and the lungs, many kinds of cancer, and with some drugs), your body makes too much anti-diuretic hormone causing you to keep too much water in your body.

A high blood sodium level is referred to as hypernatraemia and is almost always due to excessive loss of water (dehydration) without enough water intake. Symptoms include dry mucous membranes (mouth, eyes etc.), thirst, agitation, restlessness, acting irrationally, and coma or convulsions if levels rise extremely high. In rare cases, hypernatraemia may be due to increased salt intake without enough water, Cushing's syndrome, or too little anti-diuretic hormone (called diabetes insipidus).

If you've had test result for sodium, this example form may help you understand them.

In this report, seven tests have been performed as a group. They each measure a different substance in the blood that can indicate a possible health problem if levels are shown to be too high or too low.

In this hypothetical case, the purpose of the test is to monitor the electrolytes of a patient, Paul Harding, who has come in to see her GP because he has had diarrhoea and vomiting for the last three days. She has not been able to hold down much food or drink and has a very dry mouth and is very thirsty.

What the results mean

Two sets of results are shown from tests that have been performed over a six-month period.

Who prepares your test results report?

Your tests will have been performed by scientists and/or pathologists (who are medical doctors). The pathologist-in-charge who specialises in interpreting test results and observing and evaluating biological changes to make a diagnosis, will be responsible for your report. The pathologist is also available to discuss your results with your doctor.

Is there anything else I should know?

Recent trauma, surgery or shock may increase sodium levels because blood flow to the kidneys is decreased.

Drugs such as lithium and anabolic steroids may increase sodium levels; this is uncommon with most other drugs.

Drugs such as diuretics, sulphonylureas (used to treat diabetes), ACE inhibitors (such as captopril), heparin, NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen), tricyclic antidepressants, and vasopressin can decrease sodium levels in the blood.

Check with your doctor if you have any concerns about drugs you are taking and their effect on your body.

Common questions

Most sodium comes from table salt. In Australia, we take in an average of 3 — 4 grams (3000 — 4000 mg) of sodium per day. However, you need far less than this to meet the needs of the body. The NHMRC's recommended dietary intake (RDI) of sodium is 920 — 2500 mg/day.

Yes. People who have diarrhoea, vomiting, profuse sweating, kidney disease, or congestive heart failure may have low sodium levels. The frail elderly and those with diabetes or high blood pressure may have elevated sodium levels.

Yes. During prolonged and strenuous exercise both water and sodium are lost through sweating. To maintain the correct balance of water and sodium in the body, the athlete may need not only to drink water but to ensure adequate sodium intake, whether through salty foods or specially formulated `sports drinks’.

Yes. Sodium requirements are the same for all adults.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.