What is being tested?

Tests for chickenpox and shingles are performed to detect and diagnose either a current or past infection with the virus that causes these conditions, the varicella zoster virus (VZV). Most often, testing is not necessary because a diagnosis of active infection can be made from clinical signs and symptoms, but in some patients with atypical skin lesions, a diagnostic test helps to confirm the infection. In organ transplant recipients or pregnant women, the tests may be useful to diagnose a current infection or to determine status of immunity.

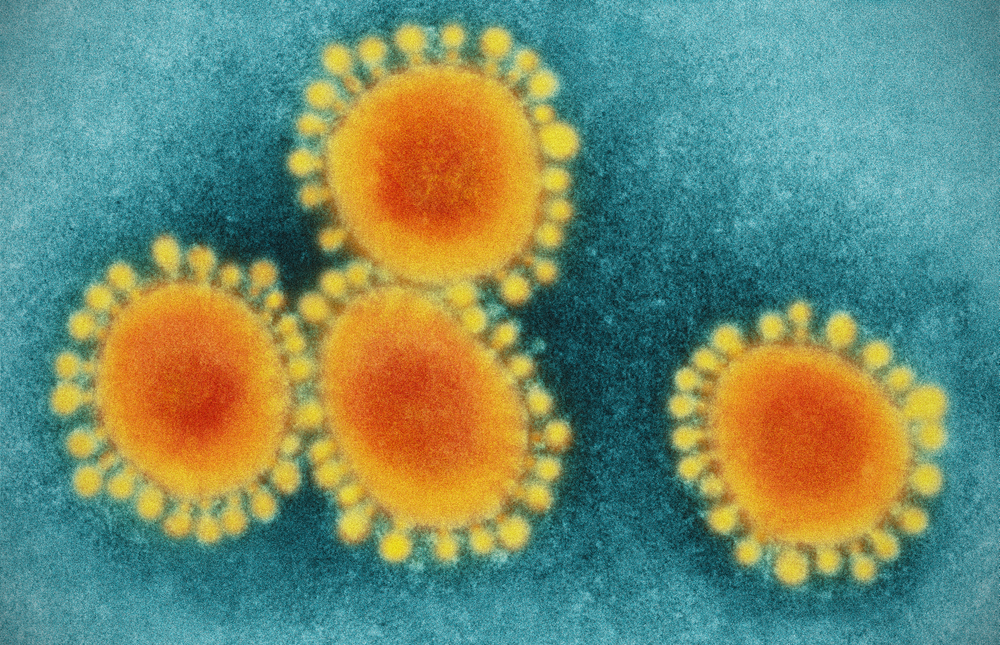

Varicella zoster is a member of the herpes virus family. It is very common and the primary infection is highly contagious, passing from person to person through respiratory secretions. VZV causes chickenpox in the young and in adults who have not been previously exposed. Usually, about two weeks after exposure to the virus, an itchy rash emerges, followed by the formation of pimple-like papules that become small, fluid-filled blisters (vesicles). The vesicles break, form a crust, and then heal. This process occurs in two or three waves or “crops” of several hundred vesicles over a few days.

Once the initial infection has resolved, the virus becomes latent, persisting in sensory nerve cells. The person develops antibodies during the infection that usually prevent them from getting chickenpox again during subsequent exposures. However, later in life and in those with compromised immune systems, VZV can reactivate, migrating down the nerve cells to the skin and causing shingles (also known as herpes zoster). Symptoms of shingles include a mild to intense burning or itching pain in a band of skin at the waist, the face, or another location. It is usually in one place on one side of the body but can also occur in multiple locations. Several days after the pain, itching, or tingling begins, a rash, with or without vesicles, forms in the same location. In most people, the rash and pain subside within a few weeks, and the virus again becomes latent. A few may have pain that lingers for several months.

Most cases of chickenpox and shingles resolve without complications. However, VZV encephalitis can occur during chicken pox with or without the presence of a rash. In immunocompromised people, such as those with HIV/AIDS or those who have had an organ transplant, chicken pox can be more severe and long-lasting, with greater risks of complications, dissemination of the virus or frequent episodes of VZV reactivation.

In pregnant women, the effects of exposure to VZV on a foetus or newborn depend on when it occurs and on whether or not the mother has been previously exposed. In the first 20 to 30 weeks of pregnancy, a primary VZV infection may, rarely, cause congenital abnormalities in the foetus. If the infection occurs one to three weeks before delivery, the baby may be born with or acquire chickenpox after birth, although the baby may be partially protected by the mother’s antibodies. If a newborn is exposed to VZV at birth and does not have maternal antibody protection, then the VZV infection can be fatal.

Before the introduction and widespread use of a varicella zoster vaccine nearly everyone became infected by VZV by the time they were an adult. While VZV is still present in its latent form in most adults, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the incidence of new cases of chickenpox in children has declined by about 90%. In Australia prior to the introduction of the varicella vaccine about 75% of children caught chickenpox by the age of 12. Since the introduction of free childhood vaccination in 2005 there has been a major decline in the incidence of new cases in children.

How is it used?

Active cases of chickenpox and shingles, which are caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), are usually diagnosed based upon the person’s symptoms and clinical presentation. Most people either have a history of chickenpox infection in childhood or have had the VZV vaccination. These people can be considered to be immune to VZV without having any further testing. However, testing for VZV or for the antibodies produced in response to VZV infection may be performed in certain cases particularly if the history of prior infection is not certain. These tests are most commonly performed in pregnant women, in newborns, in patients prior to organ transplantation, and in those susceptible to viral infections due to a weakened immune system (immune-compromised persons).

The goals for testing may include:

There are several methods of testing for VZV:

Antibody testing

When you are exposed to VZV, your immune system responds by producing antibodies to the virus. Two types of VZV antibodies may be found in the blood: IgM and IgG. IgM antibodies are the first to be produced by the body in response to a VZV infection. They are present in most individuals within a week or two after the initial exposure. IgM antibody production rises for a short time period and declines. Eventually, the level (titre) of VZV IgM antibody usually falls below detectable levels. Additional IgM may be produced when latent VZV is reactivated. IgG antibodies are produced by the body several weeks after the initial VZV infection to provide long-term protection. Once a person has been exposed to VZV, they will have some measurable amount of VZV IgG antibody in their blood for the rest of their life. VZV IgG antibody testing can be used, along with IgM testing, to help confirm the presence of a recent or previous VZV infection.

Viral detection

Viral detection involves finding VZV in a blood, fluid, or tissue sample and the diagnostic methods involved are explained below.

The choice of tests and samples collected depends on the patient, their symptoms, and on the doctor’s clinical findings.

When is it requested?

VZV antibody tests may be ordered to check immune status and/or to identify a recent infection. VZV DNA testing may be ordered on a fluid specimen coming from a vesicular rash or on blood of a newborn or immune-compromised person who has been exposed to VZV and is ill with atypical and/or severe symptoms.

What does the result mean?

Care must be taken when interpreting the results of VZV testing. The doctor evaluates the results in conjunction with clinical findings. It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between a latent and active VZV infection. This is possible for several reasons, including:

If IgG is present, the person has been exposed to VZV either through vaccination or has had chicken pox in the past. Vaccination is not 100 per cent effective and a vaccinated person can still get chicken pox. The presence of IgM taken in the right clinical context indicates either recent or active chicken pox or shingles if the person has had chicken pox previously. Shingles is a reactivation of the virus.

A diagnosis of chicken pox or shingles can be made if VZV DNA is present in the fluid coming from a vesicular rash.

Is there anything else I should know?

There is now a vaccine available for older adults that is intended to decrease the risk for having a re-activation of the virus that presents as shingles and decreases the severity of the disease if it does occur. It is not yet in widespread use and its ultimate effect on the incidence of shingles remains to be seen.

Common questions

Yes, but not as contagious as chickenpox. The infected person's vesicles contain virus, but respiratory secretions usually do not. The best way to prevent spreading shingles infection is to cover up any vesicles until they are completely dry.

Not directly. If you have never had a VZV infection or have not had the vaccine, you may come down with chickenpox the first time you are exposed to the virus. Once you have had a chickenpox infection you could develop shingles at some point in the future.

Not in most cases. Sometimes the itchy sores can become infected with bacteria when someone scratches. This may increase the likelihood of scarring.

Yes, VZV infections are found throughout the world.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.