Summary

What is your blood made of?

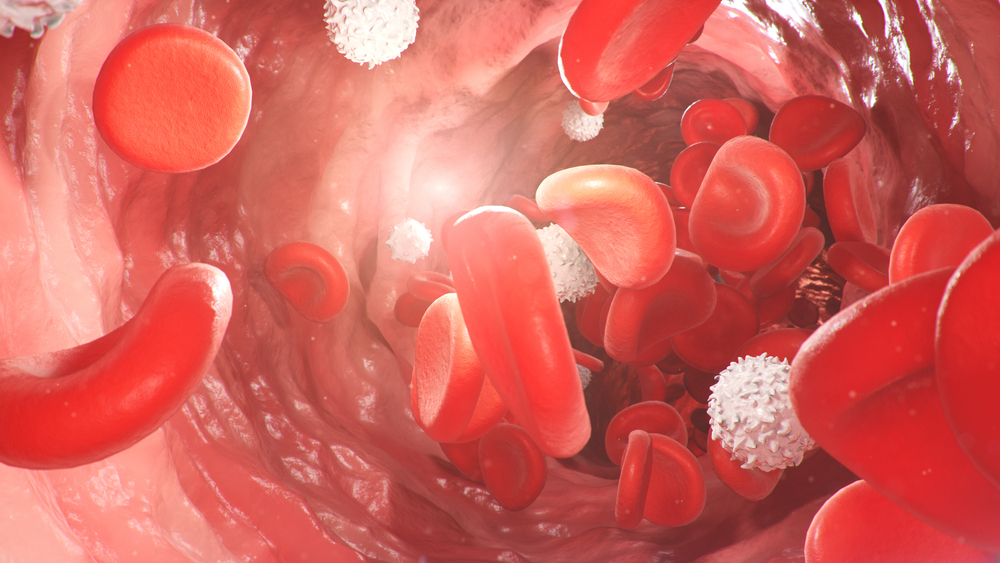

Your blood is made up of Red Blood Cells (RBCs), White blood Cells (WBCs) and platelets. These float in fluid called plasma.

Blood cells are continually being renewed

To stay healthy, your body must make new blood cells to replace those that age and degrade or are lost through bleeding.

Blood cells are continually being renewed. New cells are produced in the bone marrow, the soft fibrous tissue inside many bones, and then released into your blood stream.

Blood cells develop from stem cells and mature within the bone marrow until they are released into the blood. Red cells live for about 120 days, platelets live for about six days, and the lifespan of white blood cells depend on the type – most last for only a few hours although some last for many years.

The solid part of blood

Red blood cells (RBC)

RBCs are the most common type of blood cell – they make up almost half of your blood - and they play an essential role in carrying oxygen. All cells in every part of your body need oxygen to make energy so that they can function properly.

Red blood cells can carry oxygen because they contain haemoglobin, the red protein that gives RBCs their colour.

If your haemoglobin levels are low, or if you have too few RBCs, your body will not be able to get enough oxygen, causing fatigue and weakness.

White blood cells (WBC)

If you have an infection or inflammation somewhere in your body, your white cell production goes up. WBCs, or leukocytes, are your body’s defence against anything entering your body that can cause harm. They fight infection, help create immunity, and clean up damaged cells. WBCs are released from the bone marrow in higher amounts than normal when an infection is detected by the body. They travel in the blood to the site of infection and when they have completed their task, bone marrow production returns to normal levels.

There are five types of WBCs, all with different functions:

Platelets

Platelets are tiny plate-shaped cells that circulate in your blood. They bind together to form clots when blood vessels are injured. These clots create a temporary plug in broken blood vessels to stop bleeding.

When they become activated, they change their shape by growing long tentacles and stick to each other. Platelets also release chemicals to attract more platelets and other cells, setting off the next step in what is called the coagulation cascade.

The liquid part of blood

Plasma

This is a pale-yellow liquid that represents about half of the content of whole blood. It contains water, salt and proteins that help blood to clot, transport nutrients, minerals and hormones throughout your body.

Why get tested?

The FBC helps to screen, diagnose and monitor a wide range of disorders and conditions such as anaemia, blood clotting problems, infections, blood cancer and immune system disorders.

What does the FBC examine?

Each test in the FBC gives different information. Looked at together, along with your symptoms and medical history, they help build a picture of the health of your blood.

| Your test results report will contain information about some or all these tests. | |

| White blood cell tests | |

| White blood cells | These fight infection and are part of your immune response. The WBC count measures the total number of WBCs. Both increases and decreases in WBC numbers can be signs of health problems. |

| White blood cell differential | This looks at the different types of WBCs. There are several, each with their own job to do. Some fight bacteria, some are involved in allergies, while others make antibodies. Increased numbers of particular WBCs can help pinpoint whether an infection is caused by a bacteria or virus. Some types of blood cancer cause lots of one type of WBC to be made, meaning the other cell types cannot be made properly. |

| Red blood cell tests | |

| Red blood cell (RBC) count | RBCs carry oxygen around the body. The RBC count measures RBC numbers. |

| Haemoglobin (Hb) | This is the iron-containing, oxygen-carrying protein in red cells. Low haemoglobin levels mean you have anaemia. |

| Haematocrit (Hct) | This measures the percentage of RBCs in the blood and is often used to test for anaemia or polycythaemia (a high concentration of RBCs in your blood). |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) | MCV measures the average size of your RBCs. It is high when your cells are larger than normal (macrocytic) such as in vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, liver disease or hypothyroidism (when your thyroid gland is not making enough hormones). When the MCV is low, your RBCs are smaller than normal (microcytic) as in iron deficiency anaemia and the inherited condition, thalassaemia. |

| Mean cell haemoglobin (MCH) | This is calculated by dividing the total amount of haemoglobin by the total number of RBC in a blood sample. This gives the average amount of haemoglobin inside each RBC. The MCH is increased in macrocytic anaemias (larger red blood cells) and decreased in microcytic anaemias (small red blood cells). |

| Mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) | This is calculated by dividing the total amount of haemoglobin by the amount of space RBCs are taking up in your blood sample (the volume of RBCs). It shows the concentration of haemoglobin inside a red blood cell and takes into account the cell's volume. This can give more detail about your condition. |

| Red cell distribution width (RDW) | RDW is a calculation of how much variation there is in the size of your RBCs. If all red cells are about the same size, you will have a normal RDW. If there is a wide mix of small and large red cells you will have a high RDW. |

| Reticulocyte count | RBCs that are not yet fully developed are known as reticulocytes. Most red blood cells are fully mature before they are released from the bone marrow into the blood, but a tiny number of RBCs are released as reticulocytes. A reticulocyte count can help show if your bone marrow is making enough RBCs and gives information that will help identify causes of anaemia. |

| Platelet tests | |

| Platelet count | Platelets are important in blood clotting. Too few of them can lead to bruising or bleeding. If your platelet count is too high, blood clots can form in your blood vessels. This can block blood flow through your body. |

| Mean platelet volume (MPV) | MPV measures the average size of your platelets. Newly formed platelets are larger than older ones. A high MPV means your platelets are larger than average. If you have a low platelet count and a high MPV, it suggests that the bone marrow is quickly making new platelets, possibly because they are being destroyed. |

Having the test

Sample

Blood.

Any preparation?

None.

Your results

Reading your test report

Your results will be presented along with any other tests your doctor ordered on the same form. You will see separate columns or lines for each of these tests. Your results may be flagged as high (H) or low (L).

Reference intervals - comparing your results to the healthy population

Your results will be compared to reference intervals (sometimes called a normal range).

Reference intervals for the various components of the FBC vary slightly between laboratories in Australia because they use different measurement instruments. Always check your specific laboratory’s ranges.

Key components like Hb, RBC, HCT, WBC and platelets have distinct ranges depending on age, gender and factors like pregnancy, altitude and smoking.

Further testing

The FBC is performed on laboratory analysers that automatically count the different components. If some of your results are unclear, the laboratory may go on to perform a blood film in which a scientist or haematologist (pathologist) examines your blood under a microscope. They look more closely at the appearance of the blood cells, such as size, shape and colour, searching for anything unusual.

Any more to know?

There is no way you can directly raise the number of your WBCs or change the size or shape of your RBCs. Addressing any underlying diseases or conditions and following a healthy lifestyle will help optimise your body's cell production and your body will take care of the rest.

Questions to ask your doctor

The choice of tests your doctor makes will be based on your medical history and symptoms. It is important that you tell them everything you think might help.

You play a central role in making sure your test results are accurate. Do everything you can to make sure the information you provide is correct and follow instructions closely.

Talk to your doctor about any medications you are taking. Find out if you need to fast or stop any particular foods or supplements, as these may affect your results. Ask:

More Information

Pathology and diagnostic imaging reports can be added to your My Health Record. You and your healthcare provider can now access your results whenever and wherever needed.

Get further trustworthy health information and advice from healthdirect.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.