Summary

What are white blood cells?

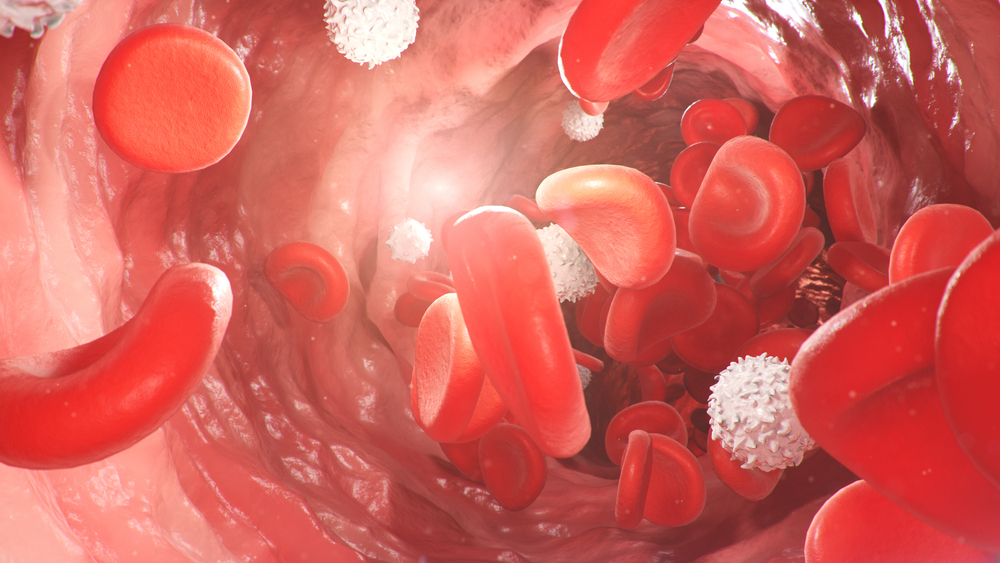

White blood cells, also called leukocytes, are part of your immune system. They help your body fight infection and other diseases, including cancer.

They are made in your bone marrow – the spongy material inside your bones. From here, they are released into your blood where they circulate in your bloodstream and lymphatic system. White blood cells travel to wherever they are needed such as when an unfamiliar organism (bacterial, viral, fungal) or particles (like allergens) enters your body, or you are injured.

What is your lymphatic system?

Your lymphatic system is a network of organs, vessels and tissues that work together to move a colourless, watery fluid called lymph from your tissues into your blood.

Your blood is made up of red and white cells which float in a fluid called plasma. The plasma part of your blood seeps out of blood vessels into surrounding tissues. In this way, tissues get nutrients and oxygen. The fluid that is left behind is lymph. Your lymphatic system soaks this up and takes it back into your bloodstream.

It does this through a network of tubes, called lymph ducts, and lymph nodes which are little bean-shaped organs clustered at your neck, armpits, abdomen and groin. Your lymph system drains extra fluid from your body and traps potentially harmful things like viruses, bacteria, fungi, cancer cells and parasites. Your lymph systems activates your immune response when substances that are foreign to your body are detected. Your tonsils and adenoids are part of this system.

The different types of white blood cells and what they do

Your bone marrow is constantly making new white blood cells because most of them have only a short lifespan – they last for as little as a few hours or a few days. About 100 billion white blood cells are made each day.

White blood cells come in many different shapes and sizes. Each type has specific role in the immune response. There are five main types of white blood cells:

White blood cells are divided into two groups: granulocytes which have small granules that release enzymes to digest microorganisms, and agranulocytes that lack these granules and typically have different functions in the immune system, such as making antibodies. Each type of granulocyte and agranulocyte plays a different role in fighting infection and disease.

Neutrophils

These are the most common type of white blood cell, and they have a short lifespan which means the bone marrow must be constantly making new replacements to maintain protection against infection. Neutrophils are the body’s first line of defence and when an infection or injury occurs, they travel to the area where they can squeeze through the narrow gaps between blood vessel cells to reach the site of infection or injury. They engulf and ingest the harmful pathogen (bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites).

Neutrophils help start inflammation and tissue repair. Inflammation is an important part of the healing process. The immune system releases substances that make your blood vessel walls more permeable – leakier - allowing more fluid to escape into the surrounding tissues and increasing blood flow to the affected area. This causes the swelling that comes with inflammation.

Lymphocytes

All cells have markers called antigens on their surface. These antigens act as identification tags, allowing cells to be recognised by other cells. Your immune system protects you by attacking infections and other substances that are foreign to your body and could be harmful to you. It does this by targeting cells with marker antigens that are different from your own.

Monocytes

Similar to neutrophils, monocytes migrate to the site of infection, and engulf and destroy harmful pathogens like bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. They help regulate the immune response by signalling to other immune cells. They help clear away dead cells and debris at injury sites.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils help fight off infections, especially parasites. They also play a role in the growth of cancer, preventing it in some cancers while encouraging it in others. In cancers like colorectal and bladder cancer, eosinophils release proteins that can kill cancer cells directly and are often linked to better outcomes. In other cancers, such as Hodgkin lymphoma, eosinophils may promote tumour growth by helping to form new blood vessels and suppressing other immune cells. In allergic reactions, eosinophils release substances that cause inflammation.

Basophils

Basophils help defend your body from infectious pathogens, but they are most known for triggering allergic reactions. They release substances like histamine and prostaglandins which causes blood vessels to dilate and become more permeable, leading to inflammation and redness. They also release heparin, which helps prevent blood clots. Basophil activation can sometimes cause anaphylaxis, a serious allergic reaction.

Mast cells

These are a type of white blood cell and work together with basophils and eosinophils in allergic reactions. However, they are not included in the white cell count because most mast cells are stored in tissue and very few are found in the blood. Mast cell activation can sometimes cause anaphylaxis, a serious allergic reaction.

Why get tested?

These tests are usually performed as part of a Full Blood Count (FBC) which assesses all the cells in your blood. They can also be used to:

Having the test

Sample

Blood.

Any preparation?

None.

Your results

Your results will be presented along with those of your other tests on the same form. You will see separate columns or lines for each of these tests.

Reference intervals - comparing your results to the healthy population

Your results will be compared to reference intervals (sometimes called a normal range).

If your results are flagged as high or low this does not necessarily mean that anything is wrong. It depends on your personal situation.

Reference intervals for the various components of the white blood cell count vary between labs so you will need to go through your results with your doctor.

Reference intervals

| High white blood cells (also known as leukocytosis) |

| White blood cell levels of 11.0 - 17.0 x 109/L cells (adults) seen in mild to moderate leukocytosis. |

Possible causes

|

| The reference intervals are typically expressed as both absolute counts (cells/µL or cells/mm³) and percentages of the total white cell count. |

| Low white blood cells (also known as leukopenia) |

| White blood cell levels of 3.0 - 3.5 x 109/L cells (adults) seen in mild to moderate leukopenia. |

Possible causes

|

| The reference intervals are typically expressed as both absolute counts (cells/µL or cells/mm³) and percentages of the total white cell count. |

A white cell count alone typically cannot diagnose any of these conditions, but abnormal levels can provide important evidence to build up a complete picture. Follow-up tests are often needed.

| White cell differential reference intervals (adults) (number of cells per volume). | |

| Neutrophils | 2.0 - 7.5 cells/mm³ |

| Lymphocytes | 1.5 - 4.0 cells/mm³ |

| Monocytes | 0.2 - 0.8 cells/mm³ |

| Eosinophils | 0.04 - 0.4 cells/mm³ |

| Basophils | Less than 0.1 cells/mm³ |

| Reference intervals can vary slightly between different laboratories. White blood cell differential results should always be interpreted in the context of your overall clinical picture, including symptoms, medical history and other test results. | |

More to know?

White blood cell counts can vary due to illness and increased levels can even be caused by eating, physical activity and stress. Someone in their final month of pregnancy or in labour may have increased levels. Removal of the spleen also leads to mild to moderate increases in white blood cells.

White blood cell counts are dependent upon age so generally normal newborns and infants have higher counts than adults. Sometimes, the elderly may fail to develop an increase in white blood cell counts in response to infection.

Questions to ask your doctor

The choice of tests your doctor makes will be based on your medical history and symptoms. It is important that you tell themeverything you think might help.

You play a central role in making sure your test results are accurate. Do everything you can to make sure the information you provide is correct and follow instructions closely.

Talk to your doctor about any medications you are taking. Find out if you need to fast or stop any particular foods or supplements. These may affect your results. Ask:

More information

Pathology and diagnostic imaging reports can be added to your My Health Record. You and your healthcare provider can now access your results whenever and wherever needed.

Get further trustworthy health information and advice from healthdirect.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.