What is being tested?

Coagulation factors are proteins that are essential for blood clot formation. Produced by the liver or blood vessels, the coagulation factors are continuously released into the bloodstream. When an injury occurs these factors are activated in a step by step process called the coagulation cascade. This cascade has two branches: when damage occurs to tissue, the body responds by activating the extrinsic pathway followed by the intrinsic pathway. Each of these pathways utilises different coagulation factors but both come together to complete the clotting process in the common pathway.

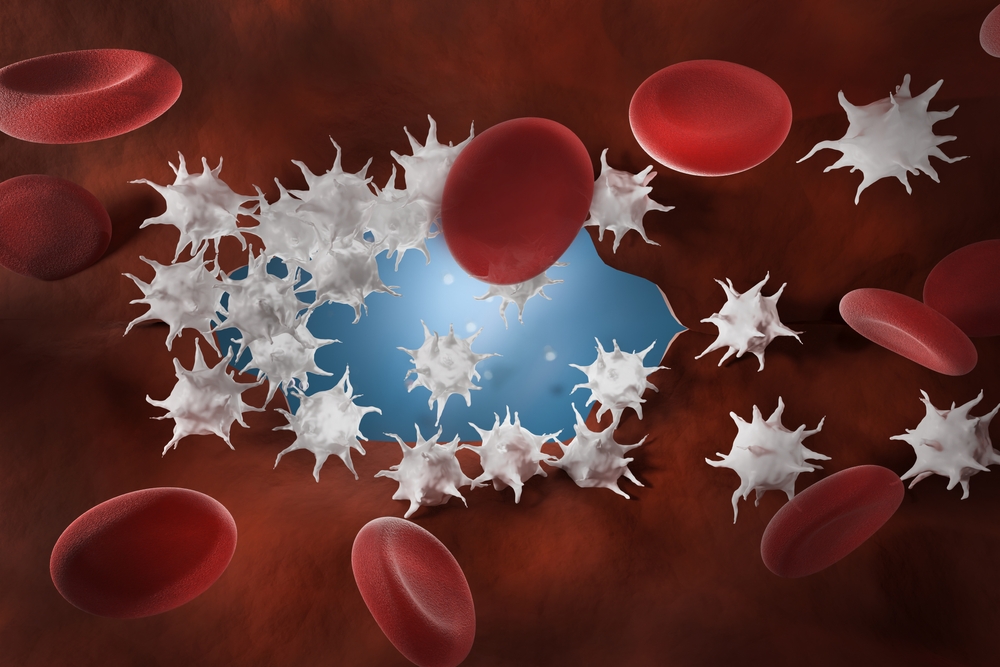

Normally, by the end of the common pathway soluble fibrinogen (factor I) has been changed into insoluble fibrin threads which form a mesh-like structure. The fibrin mesh along with aggregated cell fragments called platelets, forms a stable blood clot. Blood clots are red in colour because red cells are caught in the mesh. This barrier prevents additional blood loss and remains in place until the area has healed. When the clot is no longer needed other factors are activated to dissolve and remove it.

TYPES OF FACTOR DEFICIENCIES

About 12 of the 20 different factors involved in the coagulation cascade are vital to normal blood clotting. These 12 have individual names but are often referred to by their number, for instance factor VIII (factor 8; fVIII). When one or more of these factors are missing, produced in too small a quantity, or are not functioning correctly they can cause excessive bleeding and lead to bleeding disorders.

Deficiencies in coagulation factors may be acquired or inherited, mild or severe, permanent or temporary. Those that are inherited are rare and tend to involve only one factor, which may be partly or completely deficient or not functioning correctly. Haemophilia A and B are the most common examples of inherited disorders. Haemophilia A is a defect or deficiency of factor VIII and Haemophilia B is a defect or deficiency of factor IX. They are X-linked deficiencies (located on an X chromosome) of factors VIII and IX that occur almost exclusively in men (women are usually asymptomatic carriers). Other inherited factor deficiencies are not associated with the X chromosome and are much rarer than Haemophilia A and B.

The severity of symptoms experienced by a patient with an inherited factor deficiency depends on which factor is involved, how much of it is available and whether or not it is functioning normally. Symptoms may vary from episode to episode, from a minor prolonged nosebleed to severe recurrent bleeding into areas such as the joints. While a patient may not have trouble with a small puncture or cut, a surgery, dental procedure, or trauma could put them into a bleeding crisis. Those with severe factor deficiencies may have their first bleeding episode very early, for example a male infant with a factor VIII deficiency may bleed excessively after circumcision. On the other hand, patients with mild bleeding disorders may experience few symptoms and may discover their deficiency as an adult - after a surgical procedure or trauma, or during a screening that includes a PT or APTT test.

Acquired deficiencies may be due to chronic disease, such as liver disease or cancer; to an acute condition such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which uses up clotting factors at a rapid rate); or to a deficiency in vitamin K (the production of factors II, VII, IX, and X requires vitamin K). They may also be due to anticoagulant medications such as warfarin. Acquired conditions may involve multiple factor deficiencies that must be identified and addressed.

How is it used?

Factor testing is usually done as a follow-up to abnormal prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) testing or if you experience abnormal bleeding. These tests are used as screening tools to determine whether or not someone’s clotting cascade is functioning normally. The PT is associated with the extrinsic pathway, the APTT with the intrinsic pathway. If one or both are abnormal, the suspected coagulation factor deficiencies they suggest may then be tested for individually.

Additional testing may be done, especially when multiple deficiencies are involved, to look for underlying health problems that may be causing an acquired deficiency. If an inherited deficiency is suspected, other family members may also be tested to help confirm the patient’s diagnosis, and to establish whether they may be carriers of the condition or have the deficiency themselves (in an asymptomatic or less severe form).

Sometimes factor testing may be done on a patient with a known deficiency to monitor the factor deficiency and to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. If the patient has an acquired condition, factors may sometimes be monitored to see if they have worsened (with a progressive disease) or have got better because of treatment of the underlying condition.

When is it requested?

Coagulation factor tests may be ordered when someone has a prolonged PT or APTT and/or when they are experiencing excessive bleeding or bruising. Patients may be tested when they have a suspected acquired condition that is causing bleeding, such as DIC, pregnancy-related eclampsia, liver disease or a vitamin K deficiency.

Factor testing may be done if an inherited factor deficiency is suspected, especially when bleeding episodes begin early in life or when a close relative has an inherited factor deficiency.

Both functional factor testing (activity) and quantity testing (antigen) may be done to evaluate the severity of the deficiency. These may be monitored if the patient is undergoing treatment for a severe bleeding episode or is planning a surgery or dental procedure.

What does the result mean?

Low concentrations and/or activity of one or more coagulation factor usually means impaired clotting ability. Each coagulation factor must be present in sufficient quantity in order for normal clotting to occur but the level required is different for each factor. Results are frequently reported out as a percentage of an established normal (considered to be 100% for that factor), for instance a factor VIII that is 60% of normal.

If the APTT is abnormal and the PT is normal, you may have deficiencies of factors VIII, IX, XI, or XII.

If the APTT is normal and the PT is prolonged, you may have a deficiency of factors I, II, V, VII, or X.

If both PT and APTT are abnormal, you may have deficiencies in the common pathway or to multiple factor deficiencies.

Elevated levels of several factors are seen in situations of acute illness, stress or inflammation. In general, they are not thought to be associated with particular disease states although in some cases (such as elevated fibrinogen) they may raise the risk of developing thromboses (inappropriate blood clots).

Normal coagulation factor concentrations and activity usually mean normal clotting function. If the quantity of a factor is adequate but the activity level is low, it may mean that the factor is not functioning properly. If the factor activity is normal, but the quantity is low, it may mean that there is something interfering with its production or that something is inhibiting the factor (such as an antibody against the factor) or that it has been temporarily used up by the body.

If more than one clotting factor is decreased, it is usually due to an acquired condition such as liver disease or vitamin K deficiency.

Is there anything else I should know?

Treatments vary according to the type and cause of deficiency. For inherited factor deficiencies, the missing factor(s) – once identified – can be replaced as needed by regular injections of small volumes of concentrated factor. Acquired defiencies, in some cases may be treated with transfusion of fresh ‘normal’ plasma which contains all of the missing factors, with a concentrated cryoprecipitate. A drug called DDAVP may be used to treat a bleeding episode and as a temporary preventative measure, to provide protection against excessive bleeding during an upcoming surgery or dental procedure.

When testing coagulation factors, proper sample collection and timely processing are essential. Some of the factors are labile, meaning their concentration will decrease in the blood sample over time.

Common questions

von Willebrand factor is responsible for helping platelets stick to the injured blood vessel wall and to each other (aggregation – essential to normal blood clot formation). A deficiency in von Willebrand factor can cause von Willebrand’s disease, a relatively common inherited bleeding disorder, and it can cause a secondary decrease in factor VIII concentrations. While von Willebrand factor may be ordered along with coagulation factors if an inherited factor deficiency is suspected, it is usually considered separately because it is associated with platelets and not part of the classic coagulation cascade.

The severity of bleeding depends on the individual – how low is their factor concentration and how normally does it function – as will as which factor is deficient. Those who have a missing factor or one with very low activity will have more severe versions of the disease. People with mild deficiencies may lead a relatively normal life, requiring treatment only during surgery or severe trauma such as a motor vehicle accident.

What is Pathology Tests Explained?

Pathology Tests Explained (PTEx) is a not-for profit group managed by a consortium of Australasian medical and scientific organisations.

With up-to-date, evidence-based information about pathology tests it is a leading trusted source for consumers.

Information is prepared and reviewed by practising pathologists and scientists and is entirely free of any commercial influence.